While the Iranian government, for much of the twentieth century, attempted to settle of tribes still practicing at least partial nomadism. This involves part of the tribe migrating to progressively higher ground in the spring and summer to find fresh pasturage for their flocks, and then returning to the lowlands for the cold season. Parts of each tribe remain sedentary, growing cereal crops for survival over the winter. Eventually this way of life will probably become extinct, as migrating nomads have always been problematic for governments. Nomads have been difficult to control, and their lifestyle has led to a certain independence from central authority. It also has led to rugs with different visual flavor from those of the Persian villagers, consequently varied kinds of nomadic Persian rugs have held a special appeal for carpet lovers from across the world.

Boustani is proud to introduce to you some main Iranian tribes as the largest creators of nomadic rugs with their own styles.

Bakhtiari

The Bakhtiaris are a large and powerful tribe of over 1,200,000 who inhabit an area west and south of Isfahan along the eastern slopes of the Zagros Mountains. They have long played an important part in the history o Persia. Generally they have been more prosperous than other nomad groups. A side from the roughly twenty percent who are still seminomadic, most Bakhtiaris sedentary lives in farming villages. The land is rich and relatively well watered.

Some questions has existed as just who makes the rug known as Bakhtiaris. The weaving is generally not done by Bakhtiaris at all, but by villagers of Turkic descent who inhabit the Chahar Mahal, which is the part of the Bakhtiari domain bounded by the Zayanderud River on the north, the Zagros to the west and south, and the Isfahan plain to the east. The rug making takes place in approximately twenty villages in the vicinity of Shahr-e Kord, which is the principal market place and weaving center. The great bulk of Bakhtiaris to the north and west apparently do not weave commercially salable rugs, although much wool must come from this source. Sheep all along the eastern Zagros produce a heavy, lustrous wool that makes excellent carpets.

In older Bakhtiari specimens the warp and weft were both of wool, but newer rugs have a cotton foundation and are generally more coarsely knotted. Symmetrical knot is always used, and the weft crosses only once between each rows of knots. (This has also changed recently in some rugs to a double weft.) The pile is thick, and the sides are finished with a double overcast of thick yarn. The newer rugs are similar in weight and texture to a contemporary rugs from Hamedan, although they are readily distinguishable by pattern.

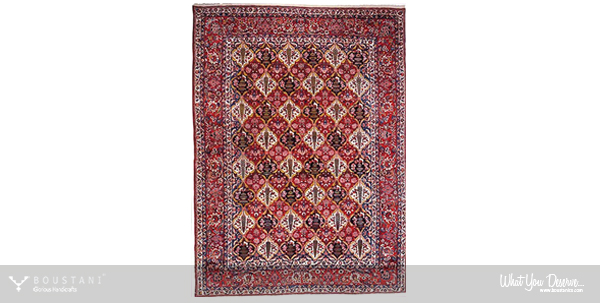

Most commercially Bakhtiari pattern involve the use of rectangular or lozenge-shaped panels, but there is some borrowing from neighboring areas which use medallion designs. Almost always the drawing is rectilinear, as scale paper is not used. A notable exception is the curvilinear medallion type now woven in Shahr-e Kord itself; this also tends to be finer than other Bakhtiaris. Another gracefully curvilinear class is the European-inspired floral fug, similar in design to some late 19th century Kerman, Bidjar, and Karabagh carpets. Apparently this type died out before World War II. Quite possibly they were a workshop rug, and Shahr-e Kord is a likely origin.

Genuinely old Bakhtiari rugs are rare, and apparently they were not imported into the United States until the 1920s.

They are marketed in Isfahan, where one finds piles of these crudely knotted, brightly colored rugs in the bazaar. The two common panel designs are everywhere to be seen in the shops and teahouses of the city. One of the larger Isfahan hotels has a long corridor in which over fifty of these panel design rugs (almost identically) are placed end to end. After examining hundreds of such rugs, one notices that the red shaded so dominant in many Persian weaves are less frequent in the Bakhtiaris, where one is struck by the prominent greens, blues and ivory.